Crinoids

Because many crinoids resemble flowers, with their cluster of waving arms atop a long stem, they are sometimes called sea lilies. But crinoids are not plants. Like their relatives—starfishes, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, and brittle stars—crinoids are echinoderms, animals with rough, spiny surfaces and a special kind of radial symmetry based on five or multiples of five.

Crinoids have lived in the world's oceans since at least the beginning of the Ordovician Period, roughly 485 million years ago. They may be even older. Some paleontologists think that a fossil called Echmatocrinus, from the famous Burgess Shale fossil site in British Columbia, may be the earliest crinoid. The Burgess Shale fossils date to the Middle Cambrian, well over 500 million years ago. Either way, crinoids have had a long and successful history on earth.

Crinoids flourished during the Paleozoic Era, carpeting the seafloor like a dense thicket of strange flowers, swaying this way and that with the ocean currents. They peaked during the Mississippian Subperiod, when the shallow, marine environments they preferred were widespread on several continents. Massive limestones in North America and Europe, made up almost entirely of crinoid fragments, attest to the abundance of these creatures during the Mississippian. Mississippian rocks crop out only in the extreme southeast corner of Kansas, but crinoid fossils are common in Pennsylvanian and Permian rocks in the eastern part of the state.

Crinoids came close to extinction toward the end of the Permian Period, about 252 million years ago. The end of the Permian was marked by the largest extinction event in the history of life. The fossil record shows that nearly all the crinoid species died out at this time. The one or two surviving lineages eventually gave rise to the crinoids populating the oceans today.

Based on the fossil record of crinoids, especially the details of the plates that made up the arms and calyx, experts have identified hundreds of different crinoid species. Though most crinoids had stems, not all did. Today, stemless crinoids live in a wide range of ocean environments, from shallow to deep, whereas their relatives with stems normally live only at depths of 300 feet or more. These modern crinoids are an important source of information about how the many different extinct crinoids lived.

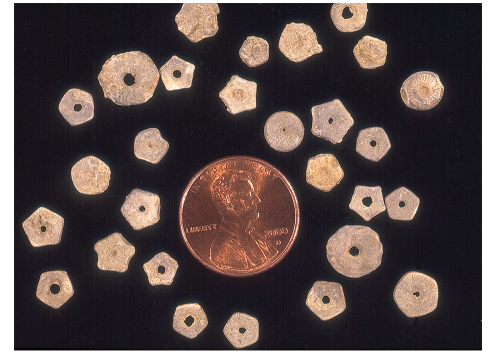

Rarely are crinoids preserved in their entirety: once the soft parts of the animal decayed, sea currents generally scattered the skeletal segments. By far the most common crinoid fossils are the stem pieces. These are abundant in eastern Kansas limestones and shales. Only occasionally is the cuplike calyx found. Kansas, however, is home to a spectacular and rare fossil crinoid called Uintacrinus, which was preserved in its entirety. These fossils, which were discovered in the Niobrara Chalk of western Kansas, lived during the later part of the Cretaceous Period, roughly 75 million years ago. Uintacrinus is a stemless crinoid, and specimens of these beautifully preserved crinoids from Kansas are on display in many of the major museums of the United States and Europe.

Stratigraphic Range: Ordovician (or possibly Middle Cambrian) to Holocene.

Taxonomic Classification: Crinoids belong to the Kingdom Animalia, Phylum Echinodermata, Subphylum Crinozoa, Class Crinoidea.

Text and photos from Windows to the Past: A Guidebook to Common Invertebrate Fossils of Kansas, Kansas Geological Survey Educational Series 16.

Sources

BBC, 2001, The Extinction Files: The End Permian Extinction (March 9, 2001).

Boardman, R. S., Cheetham, A. H., and Rowell, A. J., 1987, Fossil Invertebrates: Boston, Blackwell Scientific Publications, 713 p.

Clarkson, E. N. K., 1979, Invertebrate Palaeontology and Evolution, 3rd Edition: London, Chapman and Hall, 434 p.

Johnson, K. B., and Stuckey, R. K., 1995, Prehistoric Journey—A History of Life on Earth: Boulder, Colorado, Denver Museum of Natural History and Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 144 p.

Meyer, D. L., Mison, C. V., and Webber, A. J., 1999, Uintacrinus—A riddle wrapped in an enigma: Geotimes, August 1999, p. 14-16.

Moore, R. C., Lalicker, C. G., and Fischer, A. G., 1952, Invertebrate Fossils: New York, McGraw-Hill Book Co., 766 p.

University of California Museum of Paleontology, 1995, Brachiopoda—Fossil Record (June 29, 2000).