Clams and Their Relatives

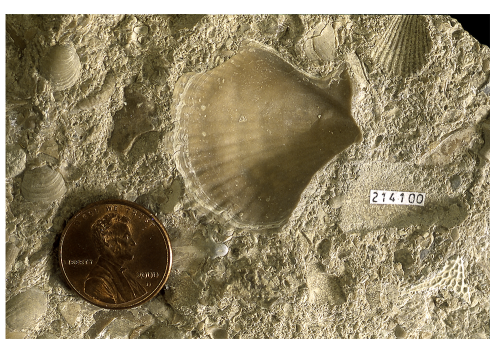

Of the fossils commonly found in Kansas rocks, clams may be the easiest to recognize because they closely resemble the shells scattered along modern seashores. Clams and their relatives (oysters, scallops, and mussels) are often called bivalves (or bivalved mollusks) because their shells are composed of two parts called valves.

Bivalves have a long history. Their fossils first appear in rocks that date to the middle of the Cambrian Period, about 510 million years ago. Although the group became increasingly abundant about 400 million years ago during the Devonian Period, bivalves really took off following the massive extinction at the close of the Permian Period.

Modern bivalves live in a variety of marine and freshwater environments, from the shallow waters near shore to great depths in the ocean. Fossils indicate that bivalves have occupied most of these environments for more than 450 million years, but during the Paleozoic Era they were especially common in near-shore environments.

Like their living descendants, fossil bivalves come in many different shapes and sizes. Externally, the valves have a wide range of markings. Typically bivalves are bilaterally symmetrical with the right and left valves being symmetrical. Some bivalves, such as oysters, do not have symmetrical valves.

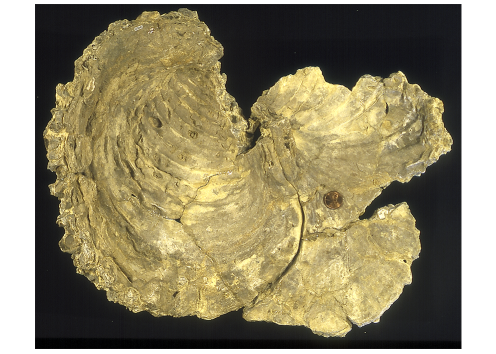

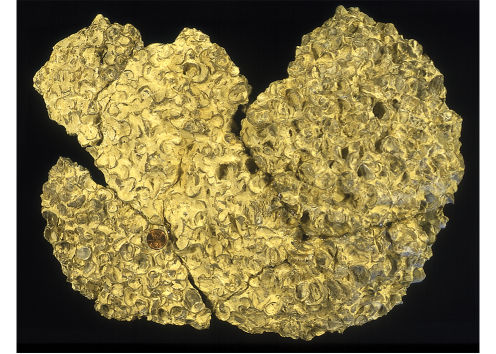

The oldest fossil clams are generally the smallest; most Cambrian species are tiny, just large enough to see without magnification. Over time, larger species evolved. The largest—inoceramid clams from western Kansas—are as much as 6 feet in diameter. These extinct clams lived in colonies on the sea floor of the shallow ocean that covered the interior of North America during the Cretaceous Period (from about 145 to 66 million years ago) and are preserved in great numbers in the rocks of the Niobrara Chalk. Some of these huge fossils are covered with encrusting oysters. Others have been found with a variety of fish fossils between their shells, indicating that the fish used the giant clam as a safe feeding place.

In addition to the huge inoceramid clams, smaller clams and oysters are also common in the Cretaceous rocks of western Kansas, particularly in the Greenhorn Limestone. In the eastern part of the state, both marine and freshwater bivalves turn up as fossils in Pennsylvanian and Permian limestones and shales.

Stratigraphic Range: Lower or Middle Cambrian to Holocene.

Taxonomic Classification: Bivalves belong to the Kingdom Animalia, Phylum Mollusca, Class Bivalvia.

Text and photos from Windows to the Past: A Guidebook to Common Invertebrate Fossils of Kansas, Kansas Geological Survey Educational Series 16.

Sources

Boardman, R. S., Cheetham, A. H., and Rowell, A. J., 1987, Fossil Invertebrates: Boston, Blackwell Scientific Publications, 713 p.

Clarkson, E. N. K., 1979, Invertebrate Palaeontology and Evolution, 3rd Edition: London, Chapman and Hall, 434 p.

Cox, L. R., 1969, General Features of Bivalvia; in, Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Bivalvia, Mollusca 6, Part N, Vol. 1, Moore, R. C., ed.: Boulder, Colorado, and Lawrence, Kansas, Geological Society of America and The University of Kansas, p. N3-N129.

Johnson, K. B., and Stuckey, R. K., 1995, Prehistoric Journey—A History of Life on Earth: Boulder, Colorado, Denver Museum of Natural History and Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 144 p.

Moore, R. C., Lalicker, C. G., and Fischer, A. G., 1952, Invertebrate Fossils: New York, McGraw-Hill Book Co., 766 p.